|

|

|

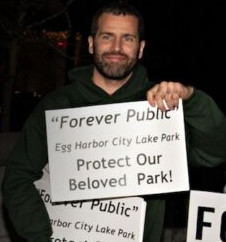

Jason Howell is the Public Lands Advocate with the Pinelands Preservation Alliance. He is a New Jersey Volunteer Master Naturalist and Wilderness First Responder. Jason creates film and video projects for PPA. Jason is a board member of the Rancocas Conservancy, a senior fellow of the Environmental Leadership Program, an avid canoeist, hiker, and wilderness skills enthusiast. |

“We were the first nation in the world to say that our most magnificent, majestic, and sacred places should not be the exclusive domain of royalty or the rich and well-connected — they should be available to everyone and for all time. That was an American idea. It was the Declaration of Independence being applied to the landscape” – Dayton Duncan author of “America’s Best Idea”

Parks and open space, and the concept of the frontier has been important part of the concept of liberty and freedom within the United States since before the revolution. Only in America, a place of untamed wilderness, did the spark of liberty grow into a flame of enduring freedom. Now that the flame has been alight for almost 250 years, we must find ways to keep fueling the fire. The fiber of the country is made from those who set out from their familiar surroundings, to points and challenges unknown. While today there may not be a new frontier beyond the horizon, we can keep that spark of courage, creativity, and imagination alive in our world-class system of national parks, forests, and state parks and forests and other areas of open space.

Wilderness is not a luxury but a necessity of the human spirit, and as vital to our lives as water and good bread. A civilization which destroys what little remains of the wild, the spare, the original, is cutting itself off from its origins and betraying the principle of civilization itself. – Edward Abbey

In European societies, even in Canada, there exists a strict hierarchical conception of land that is managed by the central government. There they call it “crown land”, or the “royal domain”, and while the public may have some elementary rights of basic use of that land, the conception is wholly different than our own National and State Parks “America’s Best Idea”. Our public open spaces are not lorded over by a king or queen, but instead are for the use and enjoyment of the public and future generations.

"The farther one gets into the wilderness, the greater is the attraction of its lonely freedom." – Theodore Roosevelt

The three part concept of property rights derived from Roman Law which help to convey the concept of rights on private and public land. There is “usus” or the right to utilize property but without alteration of that property, “fructus,” which is the right to make a profit from the use of the property, and the “abusus,” the right to significantly alter the property. When it comes to the use of especially destructive machines on public land, the damage that can be done to the space is exponentially increased compared to the visitor who arrives on foot or other human-powered or animal powered transport. This damage can accumulate rapidly without intervention and negatively affects the interest of all other citizens. In the Roman Law concept, this is an issue of those with “Usus” rights and “fructus rights”, known as usufructs, taking for themselves “abusus” rights, without compensating all of the other citizens who are also have rights.

On real private property, whether residential, commercial, agricultural or industrial there exist strong incentives for the property owner to take care of the property and the land, to prevent or control erosion, to care for the vegetation and prohibit the spread of invasive species and upkeep the buildings so that things do not fall into disrepair. If we engage in the maintenance of our private property, the value of that property is maintained or may increase and our enjoyment and use of it will be improved. If we fail to upkeep our own properties, the value may fall, our use and enjoyment of it will be negatively impacted, and our burdens increase. On real private property, the property owner most often has both the usus, fructus (the fruits), and abusus rights (the right to significantly alter).

A renter however, occupying that same land, does not necessarily have the same incentives as the property owner nor do they have the same rights. Depending on the lease or rental agreement, the renter may only have “usus” rights or in the case of agricultural land, “usus and fructus”, rights. Their incentive is only to fulfill the obligation of their lease and to extract what value they can under the agreement. While some may act morally in the improvement and maintenance of the property above and beyond their lease condition, they do not have a specific incentive to do so beyond their own morals or standards. Without a legally binding lease agreement, whereupon the property owner can recover the cost of either purposeful or incidental damage to the property, the renter has no incentive what-so-ever to be careful or considerate with the property beyond social or moral concerns. While most renters would treat the property with respect during their tenancy, a few “bad apples” doing tremendous abuse (taking abusus rights without compensation to the owner) could cost the property owner so much to make the entire proposition of rental prohibitive.

When it comes to public property, the incentive to maintain the land is even less specific than that of a renter because of a lack of a formal contract. A citizen, visiting public property, may take great care of the space they are visiting for similar social and moral concerns. However, the behavior of the visitor is wholly dependent on the social and moral demeanor of that citizen and while the vast majority do uphold the standards of behavior that most of us expect, a slim minority can cause tremendous damage, and that cost is borne by all others with a interest of the land, in this case all other citizens.

To me, a wilderness is where the flow of wildness is essentially uninterrupted by technology; without wilderness the world is a cage. – David Brower

Without intervention by a park manager acting in the place of the “landlord”, other rights holders are unlikely to intervene in what could be a contentious and costly affair for them personally. This is an example of the free-rider problem in economics. The authority on the public land, in this case the State Park Service, replaces the landlord who has a built-in incentive to maintain the property and uphold the rights of all the citizens. The Public Trust Doctrine, also dating from Roman law, replicated by English Common Law, and now enshrined in the NJ Constitution, mostly covers tidal waters in New Jersey, but the concept is clear. Citizens have a right to access public lands, but they do not have a right to use those lands in a fashion that is detrimental to the rights of others.

When it comes to off-road vehicle usage, especially illegal off-road vehicle usage, the destruction and abuse of the land and impact to other rights holders is well documented. Those who engage in the activity, are in effect “taking” and usurping for themselves abusus rights at the cost of all others. In this instance, it is the obligation of the park manager to intervene, to protect the land from wanton damage, and uphold the interest of most rights-holders. They are obligated by their position to make it difficult for abuse to take place and by creating an enforcement mechanism if it occurs despite their best efforts. Given the complexities of controlling illegal off-road vehicle activity, the land manager must be creative in the approach and balanced in the application. Finding ways to curtail abuse while allowing for non-consumptive usus rights to continue is a task that must be done carefully and artfully. While one can disagree about any one tactic employed in the endeavor, the underlying rational for protecting the rights of the citizens to have their public lands free from abuse is sound and based on the principles of liberty and property rights. This will allow a free people to maintain our essential need of open space, open minds, and the spirit of the wild.

The root issue here is that the State is a terrible manager of anything. Wharton State Forest's ecosystem, trails, and access roads were ignored for decades. Without any management, individuals jumped in and started creating their own trails and access roads. The "park managers" did nothing for decades. Now they want to jump in with the heavy hand of government make huge changes and enact huge fines for anyone who travels by vehicle on the old roads. There is a demand for off road trails in New Jersey. Much like every issue where there is a demand, yet little options exist to satisfy the demand, illegal activity will rise up to satisfy the demand. This often results in misuse. The results of closing these trails will result in more illegal activity (and ecosystem destruction) in other places. Why not provide a managed resource to meet the demand for off road travel?

Government forest funding is at the whims of politicians whose only source of revenue is to use coercion to extract funds from others to pay for things. The author is correct that owners of property have the most incentive to maintain the land properly. The employees and bureaucrats of the State Park Service do not own the land and do not have an incentive to properly care for the land. Perhaps instead a private land trust could be created that properly manages the use of this land? A private owner of the land would have the incentives to maintain the land for the future while allowing the public to use the land.